The Americans were marvelously ingenious in their exploitation of the commerce. They managed to circumvent both the East India Company's franchise and the Chinese Government's prohibition and carried on a very lucrative, if antisocial and ultimately ruinous trade. Finally, the fact of American participation in the [opium] traffic fundamentally altered the American posture in the Far East. It grew like the Southern view of slavery -- what began as an economic necessity ultimately developed into a conception of national interest with disastrous implications for the future.

Quoted from an article by Professor Jacques M. Downs, "American Merchants and the China Opium Trade, 1800-1840," published in The Business History Review, Vol. 42, No. 4 (Winter, 1968), pp. 418-442. Downs was professor of history at St. Francis College in Biddeford, Maine. (See his obituary in the September 17, 2006 Portland Press Herald / Maine Sunday Telegram.)

The entire 26-page research article (available for purchase at various websites or free from JSTOR in libraries which subscribe), from which the above quote is taken, appeared in print the same year that the assassinations of Martin Luther King, Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy ripped apart the United States. I remember that year with both horror and awe, as my own life suffered a violent philosophical wrenching so alien to what was occurring all around me. As a sophomore in high school when President Kennedy had died from assassins' bullets, I had almost completed my college courses as a major in history and government in my West Texas home by 1968. While friends and family carried on as though nothing had occurred, my life was changed forever.

|

| Courtesy of Gnostic Center |

The previous year my English lit class had studied Plato's Republic, and I felt as though I were living the scene where Socrates describes the cave-like prison where inhabitants face a wall where they view only the shadows of what is going on behind them, created by a light behind the events being played out in reality.

It was not unlike the mirror image of a world into which Alice had climbed--almost real, but not quite real. And the sound track was being provided for us daily to describe the events, that we couldn't quite trust as truth. My education was only just beginning, but it was interrupted for quite a few years of angry cynicism that kept me off-track. I did not know where to turn. I began to distrust everyone and everything. Finding my way back was a long, hard road. I watched as many of my contemporaries were sucked into Vietnam, either as war or anti-war participants. Little did we know at the time that the history about which Professor Downs had written was coming to pass.

Excerpts from "American Merchants and the China Opium Trade, 1800-1840," by Jacques M. Downs

An Existing Business Model

Most of our knowledge comes from the accounts of Europeans visiting or residing in Smyrna in the late century. More complete information apparently must await the systematic exploitation of Turkish records. [See - By far the best sources I have found to date are Salaheddin Bey, La Turquie a l'exposition universelle de 1867 (Paris, 1867) 48-56, and Carl von Scherzer, Smyrna (Vienna, 1873), 136-140. Scherzer was Austrian Consul at Smyrna for many years and should know his subject. See also O. Blau, "Etwas fiber das Opium" in the Zeitschrift der Deutschen Morgenliindischen Gesellschaft (1869), 280-281. The latter article, though very brief, cites several earlier sources in German and French. Unfortunately, neither Blau nor many of his references are readily available in this country.]

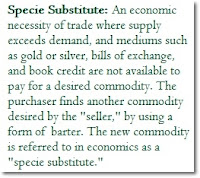

Opium was planted in late October and November and began to grow during the winter. Although the cold weather kept the plants small, the root-system developed considerably. Thus with the coming of spring, the plants would grow rapidly, each sending up from one to four stalks three or four feet high. At the end of April the poppies bloomed, and about two weeks after the petals fell, the poppy-head was fully developed and ready for harvesting....Here was a pattern which was typical in the American China trade. Precisely the same configuration had appeared in the commerce in ginseng, sealskins, sandalwood, and just about every other specie-substitute American merchants discovered. The first ships would make a killing, the scent of which would draw others into the trade until the market was saturated, and the trade ceased to pay. Thereafter, periodic gluts would occur until the supply became exhausted (as with sandalwood and fur) or until a few of the stronger firms established some sort of loose organization of the market. In the Turkish opium trade, the organizers were Perkins & Company and its allied concerns in Boston.

The crop began arriving in Smyrna toward the end of July or the first of August and continued until the following spring. [See a letter from Thomas H. Perkins to John P. Cushing, January 15, 1825, Samuel Cabot Collection, Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston.] Merchants resident at Smyrna purchased the raw opium for shipment overseas, most importantly to the Orient, though one-quarter to one-half seems generally to have gone to Europe and elsewhere.

Map of Ottoman Empire, circa 1792

In the early days of this commerce most Americans employed the good offices of the British Levant Company, since it was customary to use "the flag and the protection" of a nation which had a trade agreement with the Sublime Porte. [fn. - The United States had no formal agreement with the Porte until the Rhind Treaty of 1830. For further information, see Samuel Eliot Morison, "Forcing the Dardanelles in 1810," New England Quarterly, I (April, 1928), 208-225.] For this service, they paid "a light consulage and dragomange duty, roughly about one per cent on the value of goods imported and exported." Although the British Consul-General in Constantinople reported as late as 1809 that Americans still preferred to consign their goods to the Levant Company, the trading pattern soon began to change.

As early as the late 1790's, American vessels were calling at Smyrna but it was not until 1804 that Philadelphia and Baltimore ships began the trade in earnest. [See Charles C. Stelle, "American Opium Trade to China prior to 1820," Pacific Historical Review, IX (Dec., 1940), 430-431. See also letter from R. Wilkinson to James Madison, January 15, 1806, U.S. Department of State, Despatches from Consuls in Smyrna, I, National Archives, Washington, D.C.] Probably the first figures of any consequence in the American drug trade from Smyrna to China were James and Benjamin C. Wilcocks. The former arrived in Smyrna in 1804 as supercargo of the brig Pennsylvania. They cleared for Batavia, but both were in China by the following October. Benjamin remained, but James appears to have gone home with the ship, to return via Smyrna on the Sylph the following year with more opium. [Note: The Wilcockses sailed for their kinsmen, William Waln and R. H. Wilcocks of Philadelphia, who continued to send ships to Canton consigned to the brothers. See letter from Wilkinson to Madison, January 15, 1806; Despatches from Consuls in Smyrna. Benjamin Wilcocks remained in Canton until 1807 or 1808. He then returned home and established a business in Philadelphia but "was obliged to return . . . in 1811." See letter from John R. Latimer to Mary R. Latimer, March 30, 1830, John R. Latimer Papers, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.]

Apparently the commerce paid, for several other American China merchants immediately showed an interest. Willings & Francis sent opium aboard the Bingham in the spring of 1805, [See letters from the supercargo, William Read, in the Willings & Francis Collection, Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

The brig Eutaw, Captain Christopher Gantt, of Baltimore was in Smyrna from July to November, 1805, and then sailed for Canton with 26 chests and 53 boxes of opium aboard, and in January of the following year, Stephen Girard seems to have become excited by the possibilities of the trade. He wrote two of his supercargoes in the Mediterranean:

"I am very much in favor of investing heavily in opium. While the war lasts, opium will support a good price in China .... " [See letter from Girard to Mahlon Hutchinson, Jr., & Myles McLeveen, January 2, 1805, Stephen Girard Papers, Girard College Library, Philadelphia, Pa. on microfilm at the American Philosophical Society Library, Philadelphia.]James & Thomas H. Perkins of Boston, who had relatives in Smyrna, had inquired of their nephew at Canton as to the market for Turkish opium in China. [Note: Extracts from two letters from J. & T. H. Perkins to John P. Cushing June 19, September 23, 1805, quoted in J[ames] E[lliott] C[abot], "Extracts from the Letterbooks of J. & T. H. Perkins..." (See typewritten Manuscript, Massachusetts Historical Society, n.d.] John Cushing [See Biographical Dictionary of American Business Leaders by John N. Ingham] had gone to Canton as clerk to Ephraim Bumstead, a former apprentice in the Perkins house. Bumstead fell ill and died, and Cushing, age 16, took over. When he came of age, he was made a partner in the firm, Perkins & Company, which he had organized and run since his arrival. He proved to be a merchant of rare ability and amassed a fortune of nearly one million dollars before he finally sailed for home in 1831. Others soon joined them, and the first of a series of "opium rushes" was reported at Smyrna by Girard's disappointed agents. [See letter from Mahlon Hutchinson, Jr., & Myles McLeveen to Girard, March 30, 1806, Girard Papers.] In 1807, another Philadelphian, George Blight, reported from China that while opium "at times paid very well," it had "disappointed many the past season" because the trade had been far overdone. [See letter from Blight to Girard, March 4, November 21, 1807, Girard Papers.]

Opium As a Specie Substitute

America's War on Drugs

What we had begun to see by 1968 was a phony war against drugs. We were being told that marijuana was a gateway drug, not only highly addictive, but which would lead to even worse opiate addictions--primarily heroin. A war was necessary. Not only should all these narcotics be "controlled," but anyone who used or possessed them should be prosecuted as criminals. I was rebellious only in mind and spirit but quite conservative where behavior was concerned. I avoided all drugs, including tobacco, and had never even tasted beer or wine until after graduating college in 1970.

I lived and operated within a strange world of half-life, where I did what a good girl would do, while at the same time held those who would try to control my beliefs or actions in total and utter contempt. I knew in my gut that Lee Harvey Oswald, for example, had not killed President Kennedy, that Sirhan Sirhan was also a mind-controlled patsy, and that there was something much bigger and uglier than James Earl Ray who was responsible for killing Martin Luther King. I could not explain how I knew, but I did.

I had completed law school by 1975, while maintaining a deprecatory opinion of lawyers and a fear of being co-opted if hired by a firm of them. I shunned the adversary system which I saw as a sham that required sophistry of the highest register. I refused to argue on behalf of or support people or principles with which I disagreed. Thus I eventually found a niche within the land title and abstract industry, which seemed so close to my love of history. In time, I prospered, grew ever confident within myself, and began to meet others who shared my point of view--thanks, of course, to the internet.

It was only after meeting such folks as Kris Millegan and Catherine Austin Fitts, hearing their stories, reading and researching with them in the mid-1990's, that I was able to free the restraints that kept me from changing my position in the cave. Only with their helpful insight did I begin to look at reality head on. I can never thank them enough for allowing me to step into the world of truth where we now reside together.

We had started to realize by that time that the drug war was being fought to benefit a secret intelligence group who wanted to eliminate their competition and thus effectively create a price support floor under the commodity which paid for America's "national security" infrastructure.

So many of our research community referred to this phenomenon as "CIA Drugs," but I knew it began much earlier than the year 1947, when the CIA was born. Little did I know that Professor Downs had already discovered in 1968 that elements within our government had conceived of this use of opium as a substitute specie as being in the "national interest," or national security interest as it became to be called, and that conception would have ever more disastrous implications for us and our world.