©2006 by Linda Minor (all rights reserved)

“Squandering the people’s money even in wartime is no proof of patriotism.”

-Jesse H. Jones [1]

“He [Jesse H. Jones] was, through the New Deal and through the war, the great financial bridge between the purposes of the New Deal, and particularly the purposes of the war, and the sources of the funds to do it. It was an extraordinary grant of power. He had more control over the flow of money to the executive branch and its purposes than any congressman or any congressional committee.”

An Extraordinary Grant of Power

Jesse Jones served as the “financial bridge” between the New Deal and the war as well as the funding bridge for covert operations and propaganda that would later wage the cultural cold war.

The real story of Jesse Jones, however, begins in the closing days of World War I when Jones was appointed by Woodrow Wilson (no doubt at the instigation of fellow Texan E.M. House) to serve as Director General of Military Relief for the American Red Cross. In that role he became a protégé of Herbert C. Hoover—whose career to that point had been spent working for gold producing corporations in attempts to stabilize American currency while making lots of money.

Hoover, who would serve as U.S. President from 1929 to 1933, headed the American Commission for Relief in Belgium from London (the “Belgian Relief Fund”), the goal of which was to feed war-ravaged victors of the war without at the same time upsetting the international balance of payments.

The Brown and Root of the matter

Incredibly, there are more people who have heard of the Brown brothers (George and Herman) than there are people who know who Jesse Jones was. Herman Brown built a road-construction business in central Texas, totally dependent upon city and county government contracts. In 1926 he was joined by his brother, George R. Brown, who took Herman’s Austin-based business two hundred miles east into Houston, a virtual promise-land of dusty streets waiting to be covered by asphalt.

George quickly began moving in the right circles in Houston, while older brother Herman was hobnobbing with politicians in the State capital of Austin. For more than a decade they were content simply to pave streets and roads and build small bridges and drainage systems. Then, through Herman’s relationship with Lyndon Johnson, ambitious young New Dealer in Franklin Roosevelt’s administration, and through George’s growing contacts with friends of Jesse Jones in Houston, they succeeded in making it to the big time—contracting with the federal government.

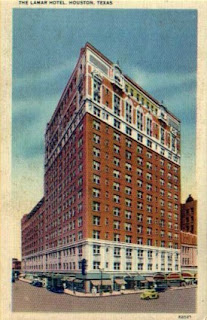

Without the necessary experience to build dams, ships or naval air stations, all they had to do was financially support the proper public officials and work with an experienced contractor to learn the ropes. Contacts made in Suite 8F—the suite Brown & Root leased at Jesse's Lamar Hotel—would make it all possible.

Jesse Jones and Suite 8F

The Lamar Hotel was one of dozens of commercial buildings Jesse Jones built in the growing Texas city of Houston, but it was in the Lamar’s penthouse where he resided after its completion in 1927. The Brown suite, eight floors below Jones’ home, became the home away from home for some of the wealthiest power brokers in Texas, who began fraternizing there in the 1930’s.

Jesse H. Jones first arrived in Houston from Tennessee in 1898 to work in his uncle’s lumber company, which he managed after his uncle (Milford T. Jones) died. T.W. House, Jr. had been president of M.T. Jones Lumber company and trained young Jesse to take over the management. Four years later, after his uncle's death, Jesse escorted his aunt Louisa Jones on a tour of Europe and London, where they attended the Coronation of King Edward VII. Before departing the U.S., they had stopped off in New York, however, to see Jesse's former Houston neighbor and erstwhile attorney at the Houston law firm Baker & Botts; Robert Scott Lovett—E.H. Harriman’s second in command at the Union Pacific and Southern Pacific Railroads—offered Jesse a financing arrangement for his future business enterprises. The Harriman empire promised to loan money to Jones at four percent interest, and in exchange for that loan, Jesse would give Harriman fifty percent of his profits. [2]

What a deal that would have been—for Harriman, at least! The documents were drawn up to be executed upon Jones' return from Europe.

Jones’ Inner Circle and Col. E.M. House

However, by the time of his return to New York, Jones declined to sign, instead announcing his plan to enter business completely on his own, foregoing partners or outside capital. That announcement, however, contains little truth. In 1907, when the economic panic hit, Jones’ lumber company owed the T.W. House Bank, which financed the construction, $500,000, mostly in long-term real estate loans.

Jones had also been an investor in 1905—alongside Col. E.M. House and his brother Thomas W. House, Jr., members of Houston’s wealthy Rice family, and Andrew Mellon of Gulf Oil in Pittsburgh—in a nationally chartered bank in Houston, the Union National Bank and Trust. [3]

|

| From the John T. Jones, Jr. collection |

The vague explanations of Jesse Jones’ ability to pull himself up from his bootstraps and create a Texas commercial empire all on his own never rang quite true. [4] He rose too high, too quickly—not even slowed by the Panic of 1907, which placed the family of fellow Houstonian “Colonel” Edward M. House in receivership. With the majority of the T.W. House private bank’s investments in illiquid property—mostly real estate, not readily convertible to cash—a receiver had to be appointed to give the bank time to sell assets in order to pay demands. The experience made Col. House a great believer in establishing a central bank—like the Federal Reserve System, which he helped create during Woodrow Wilson’s presidency. [5]

The vague explanations of Jesse Jones’ ability to pull himself up from his bootstraps and create a Texas commercial empire all on his own never rang quite true. [4] He rose too high, too quickly—not even slowed by the Panic of 1907, which placed the family of fellow Houstonian “Colonel” Edward M. House in receivership. With the majority of the T.W. House private bank’s investments in illiquid property—mostly real estate, not readily convertible to cash—a receiver had to be appointed to give the bank time to sell assets in order to pay demands. The experience made Col. House a great believer in establishing a central bank—like the Federal Reserve System, which he helped create during Woodrow Wilson’s presidency. [5]Already a millionaire by 1912 when Woodrow Wilson was elected President (an election Wilson owed entirely to the behind-the-scenes manipulations of Col. House), Jones turned down several offers to serve in the administration, finally agreeing in 1917 to become director of general military relief for the American Red Cross. In that capacity he worked closely in concert with Herbert Hoover of the Belgian Relief Fund. In those two years Jones would learn how to recreate that model into the Marshall Plan when called upon at the end of World War II.

Jesse Jones and the New Deal

Appointed first by President Hoover to head the Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC) in 1932, Jones continued into Franklin D. Roosevelt’s administration until 1940, when he was appointed Secretary of Commerce. [6] The RFC had been empowered by Congress to establish subsidiaries, and it expanded under Jones’ tenure by creating a plethora of government-owned corporations, including:

• Defense Plant Corporation

• Defense Supplies Corporation

• Metals Reserve Company

• Rubber Reserve Company

• United States Commercial Company

• War Damage Corporation

• Petroleum Reserves Corporation

• Defense Homes Corporation

By 1939 the war production corporations had been removed from RFC’s lending program, which by then consisted of domestic subsidiaries, such as the:

• Federal Loan Administration

• Federal Housing Administration

• Electric Home and Farm Authority

• Export-Import Bank

• Home Owners Loan Corporation

• Federal Home Loan Bank System.

It was Jones’ own protégé at the RFC, yet another Houstonian, William L. Clayton, [7] who would help to administer the European Recovery Program, known as the Marshall Plan, after World War II. [8]

Jesse's Break with the New Deal

Jones returned to Houston in 1945, still with a decade left to devote to his commercial activities. His first act, however, was to publish an editorial in his own Houston Chronicle, voicing what he felt was wrong with the methods being followed by his replacement at the Commerce Department, the former Vice President, Henry A. Wallace (often accused of socialism), whom Jones accused of making an unsecured loan of almost four billion dollars to Great Britain without giving thought to the effect on America’s economy.

Jones returned to Houston in 1945, still with a decade left to devote to his commercial activities. His first act, however, was to publish an editorial in his own Houston Chronicle, voicing what he felt was wrong with the methods being followed by his replacement at the Commerce Department, the former Vice President, Henry A. Wallace (often accused of socialism), whom Jones accused of making an unsecured loan of almost four billion dollars to Great Britain without giving thought to the effect on America’s economy. Notwithstanding the disaster Jones predicted (see inset box to the right), his former deputy Will Clayton, testified in hearings before the House Banking and Currency Committee several months later that Jones “did not understand the full implications of world-wide bilateral commerce as it would affect the trade of this country,” adding that “the figures Mr. Jones used in his letter to the committee earlier this week were based on a 1941 Treasury report, and that since then $1,000,000 of the assets referred to were spent ‘to keep the flag of freedom waving.’ ” [9]

Clearly, something was very wrong with the global economy in 1946. It was an age of desperation. That desperation must be fully recognized and understood in order to understand what was to follow. Less than six months after the United States dropped two atomic bombs on Japan, 1946 would become a watershed year—the beginning of an age of fear of nuclear war and continued fear of Communism for decades to come.

Back in Texas, Jesse Jones and his associates were in their heyday at the Lamar Hotel’s Suite 8F — planning how best to take advantage of those fearful times, while at the same time using all the inside information they had acquired working for the government.

Back in Texas, Jesse Jones and his associates were in their heyday at the Lamar Hotel’s Suite 8F — planning how best to take advantage of those fearful times, while at the same time using all the inside information they had acquired working for the government.That was when Brown & Root really took off, as we will see in the next episode.

ENDNOTES:

[1] Quoted in obituary appearing in the Washington Post and Times Herald (June 2, 1956).

[2] Baker & Botts is the same law firm eventually headed by James A. Baker III, (See “Course of Deception”),

whose family has controlled it since Civil War days. After 1902

Harriman would be required to divest himself of ownership of the

Southern Pacific stock, which a court found violated anti-trust

legislation.

[3]

The bank’s president, Jonas Shearn Rice, was a nephew of William Marsh

Rice (for whom the Rice Institute was named), and the father-in-law of

W.S. Farish, Sr., a founder of Humble Oil. J.S. Rice was also chairman

of Jesse Jones’ Bankers Trust, which had been incorporated during that

decade by the same law firm (Andrews, Kurth, Campbell & Jones) which

represented both Humble Oil Company and another Houstonian, Howard R.

Hughes, Jr., and with which James A. Baker III would spend much of his

career because of an anti-nepotism policy that prevented him from

working at Baker & Botts while his father was there.

[4] The Dictionary of American Biography,

for example, states: “Through his shrewd handling of money and

management, Jones was general manager of the firm by 1898. Not

satisfied with working for someone else, he organized the South Texas

Lumber Company four years later. His experience in the lumber business

led to a combination of real estate, construction, and banking

ventures—all centered in Houston. His firm erected numerous office

buildings, and his real estate dealings soon made him a millionaire.”

[5]

Col. House helped to assemble Nelson Aldrich, J.P. Morgan’s bankers

with the elite group of millionaires who frequented Jekyll Island,

Georgia—in combination with Paul Warburg, who drafted legislation

creating the Federal Reserve Banking System. (See “Membership by Inheritance Only.”)

[6] The Washington Post and Times Herald

(June 2, 1956). The names and directors of executive agencies and

corporations were forever changing. For example, in January 1941 an

executive order established the Office of Production Management, which

was replaced a few months later by the Supply Priorities Allocation

Board, itself replaced by the Office for Emergency Management (OEM) in

January 1942. OEM was responsible for coordinating the supply and

allocation of defense-related materials and commodities.

[7] According to Dictionary of American Biography, Supplement 8:

1966-1970 (American Council of Learned Societies, 1988): "Clayton’s

firm, Anderson-Clayton—the largest cotton-trading enterprise in the

world—made its expansion into markets formerly controlled by European

cotton brokers when it moved into the vacuum created at the close of

World War I. Clayton’s first government role was in 1918 as a member of

the Cotton Distribution Committee of the War Industries Board, headed

by Bernard Baruch. In 1940 he became deputy federal loan administrator

in the RFC and vice-president of the Export-Import Bank under Jesse

Jones, which in 1942 was placed under the Commerce Department. In the

summer of 1943 he was placed under the authority of Vice-President Henry

Wallace, who headed the Board of Economic Warfare. Unable to get along

with Wallace, Clayton resigned in January 1944."

[8]

The European Recovery Program is often referred to as the “Marshall

Plan,” the program discussed in “Hustlers and Hucksters”).